- Home

- Pierre Reverdy

Pierre Reverdy

Pierre Reverdy Read online

PIERRE REVERDY (1889–1960) was born in Narbonne in the south of France. At age twenty-one he moved to Paris and became close friends with the artists and writers around Montmartre, particularly with the poets Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire and the painter Juan Gris. During this time, he converted to Catholicism, founded the seminal literary magazine Nord-Sud, married the seamstress Henriette Charlotte Bureau, and began a deep and intimate friendship with Coco Chanel that would last for the rest of his life. In 1926, after publishing several books of poetry that included collaborations with Gris, Picasso, and Georges Braque, he moved with his wife to the village of Solesmes to be near the Benedictine monastery at St. Peter’s Abbey. During the Nazi occupation, he joined the Resistance, refused to publish anything, and wrote the excruciatingly brutal Le Chant de morts (Song of the Dead) that was eventually published in 1948 with illustrations by Picasso. Besides a few trips around Europe and Greece, Reverdy remained in Solesmes for the rest of his life, ever more estranged from society and from his own faith.

MARY ANN CAWS is Distinguished Professor of Comparative Literature, English, and French at the Graduate School of the City University of New York and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She is the author of dozens of books, including Glorious Eccentrics: Modernist Women Painting and Writing, The Surrealist Look, and Surprised in Translation; the editor of the Yale Anthology of Twentieth-Century French Poetry; and the translator of, among many others, André Breton, René Char, Robert Desnos, Paul Eluard, Ghérasim Luca, Stéphane Mallarmé, Jacques Roubaud, and Tristan Tzara.

Pierre Reverdy

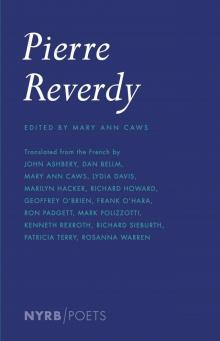

EDITED BY MARY ANN CAWS

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY

JOHN ASHBERY, DAN BELLM,

MARY ANN CAWS, LYDIA DAVIS,

MARILYN HACKER, RICHARD HOWARD,

GEOFFREY O’BRIEN, FRANK O’HARA,

RON PADGETT, MARK POLIZZOTTI,

KENNETH REXROTH, RICHARD SIEBURTH,

PATRICIA TERRY, ROSANNA WARREN

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Compilation copyright © 2013 by NYREV, Inc.

Poems from Œuvres complètes: Pierre Reverdy, volumes 1 and 2, edited by Étienne-Alain Hubert copyright © 2010 by Éditions Flammarion, Paris; poems from Main d’œuvre copyright © 1949 by Mercure de France; all other poems copyright © 2010 by Éditions Flammarion, Paris

Translations copyright © 2013 by their respective translators, with the exception of translations © 1981, 2013 by Mary Ann Caws; copyright © 2013 by Maureen Granville-Smith, Executor of the Estate of Frank O’Hara; copyright © 1969 by the Kenneth Rexroth Trust, originally published in Selected Poems by Pierre Reverdy, New Directions Publishing; copyright © 1993, 2013 by Rosanna Warren, originally published in Stained Glass by Rosanna Warren, used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.; copyright © 1974, 1991 by John Ashbery; and copyright © 2007 by Ron Padgett, originally published in Prose Poems by Pierre Reverdy, Black Square Editions

Preface copyright © 2013 by Mary Ann Caws

Chronology copyright © 2013 by Richard Sieburth

All rights reserved.

Cover design by Emily Singer

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Reverdy, Pierre, 1889–1960

Pierre Reverdy / by Pierre Reverdy ; edited by Mary Ann Caws.

pages cm. — (New York Review Books poets)

A bilingual edition with parallel text in French and English.

ISBN 978-1-59017-679-5 (pbk.)

1. Reverdy, Pierre, 1889–1960—Translations into English. I. Caws, Mary Ann, editor, translator. II. Reverdy, Pierre, 1889–1960. Poems. Selections. III.

Reverdy, Pierre, 1889–1960. Poems. Selections. English. IV. Title.

PQ2635.E85A2 2013

841'.912—dc23

2013016938

ISBN 978-1-59017-816-4

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB/Poets series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

Contents

Preface

Chronology

Translator Index

POÈMES EN PROSE / PROSE POEMS (1915)

Plus loin que là / Further Away Than There *

Toujours seul / Always Alone *

Les Poètes / The Poets *

L’Intrus / The Intruder *

Belle étoile / Under the Stars *

L’Esprit sort / The Spirit Goes Out *

Des Êtres vagues / Vague Creatures *

Voyages trop grands / Trips That Are Too Long *

Chacun sa part / To Each His Own *

Saltimbanques / Street Circus *

L’Envers à l’endroit / Backwards Forwards *

Les Pensées basses / Base Thoughts *

LA LUCARNE OVALE / THE OVAL ATTIC WINDOW (1916)

Sur l’amour-propre / On Pride *

Peine perdue / Vain Effort *

Plus tard / Later *

LES ARDOISES DU TOIT / ROOF SLATES (1918)

Auberge / Inn *

Tard dans la nuit... / Late at Night... *

Miracle / Miracle *

Secret / Secret *

Le Même numéro / The Same Number *

Fausse porte ou portrait / False Door or Portrait *

Chambre noire / Dark Room *

LA GUITARE ENDORMIE / THE SLEEPING GUITAR (1919)

Près de la route et du petit pont / Near the Road and the Small Bridge *

L’Amour dans la boutique / Love in the Shop *

Saveur pareille / Same Taste *

Quelque part / Somewhere *

Le Nouveau venu des visages / The Newest Face *

ÉTOILES PEINTES / PAINTED STARS (1921)

L’Ombre et l’image / Shade and Image *

Après-midi / Afternoon *

Mouvement interne / Inner Motion *

CRAVATES DE CHANVRE / CRAVATS OF HEMP (1922)

Verso / Verso *

La Langue sèche / Dry Tongue *

Adieu / Goodbye *

GRANDE NATURE / FULLY GROWN (1925)

Détresse du sort / Fate Founders *

Ce souvenir / That Memory *

Clair hiver / Clear Winter *

LA BALLE AU BOND / BALL ON THE BOUNCE (1928)

Au bout de la rue des astres / At the End of the Street of

Stars *

Temps de mer / Sea Weather *

Voyage en Grèce / Journey to Greece *

SOURCES DU VENT / SOURCES OF THE WIND (1929)

Comme on change / How to Change *

Nature morte-portrait / Still Life-Portrait *

Spectacle des yeux / Spectacle for the Eyes *

Un Tas de gens / A Lot of People *

Voyages sans fin / Endless Journeys *

Sur la pointe des pieds / On Tiptoe *

Perspective / Perspective *

Encore l’amour / Love Again *

Le Monde devant moi / The World Before Me *

Rien / Nothing *

La Ligne des noms et des figures / The Line of Names and

of Figures *

FLAQUES DE VERRE / PUDDLES OF GLASS (1929)

Pointe de l’aile / Tip of the Wing *

Messager de la tyrannie / Messenger of Tyranny *

Plus lourd / Heavier *

Ça / That *

...S’entre-bâille / ...Is Ajar *

Le Pavé de cristal / The Crystal Paving Stone *

D’Une autre rive / From Another Shore *

Glo

be / Globe *

Et s’en aller / And to Take One’s Leave *

Numéros vides / Empty Numbers *

En Marchant à côté de la mort / Walking Next

to Death *

L’me et le corps superposés / Body and Soul

Superimposed *

La Tête pleine de beauté / Head of Beauty *

PIERRES BLANCHES / WHITE STONES (1930)

L’Invasion / The Invasion *

Au bord du temps / At the Edge of Time *

Il devait en effet faire bien froid / It Must in Fact Have

Been Quite Cold *

FERRAILLE / SCRAP METAL (1937)

À Travers les signes / Across Signs *

LE CHANT DES MORTS / THE SONG OF THE DEAD (1948)

Au bas-fond / In the Hollow *

Le silence qui ment / The Lying Silence *

Sourdine / Noiselessly *

À voix plus basse / In a Lower Voice *

Sous le vent dur / Under the Harsh Wind *

De la main à la main / From the Hand to the Hand *

La vie m’entraîne / Life Pulls Me Along *

BOIS VERT / GREEN WOOD (1949)

Chair vive / Live Flesh *

AU SOLEIL DU PLAFOND / SUN ON THE CEILING (1955)

Figure / Figure *

Le Livre / The Book *

Pendule / Clock *

LA LIBERTÉ DES MERS / FREEDOM OF THE SEAS (1960)

Faux site / False Site *

PREFACE

Why Reverdy?

PIERRE REVERDY is among the greatest of modern French poets, and certainly among the most elusive. His work is at once impersonal and intimate, crystalline and opaque, simple to the point of austerity. The landscape of his poetry is both instantly recognizable and, devoid of local specificity, imbued with an otherworldly strangeness. He is “a secret poet for secret readers,” as Octavio Paz once described him, insisting on the necessity of parsing the silence, the empty spaces between what seems visible in the lines of his poems. Each feels like a fragment of a universe, and yet whole.

A single moment has a singular potential. “Just for Now,” in Frank O’Hara’s translation, lays the stress on that:

Life, it’s simple it’s great

The clear sun rings a sweet noise

[...]

Listen, I’m not crazy

I’m laughing at the foot of the stairway

Before the great wide open door

In the espaliered sunshine

And my arms are stretched towards you

This day that I love you

It’s today that I love you

The poet himself adamantly refused to have any chronology attached to his poems or any biographical details intruding on them. He is said to have prayed, “Let me never be well-known.” Nevertheless, Reverdy was a fixture of Montmartre bohemia and, for a few years during the heyday of his magazine Nord-Sud in 1917 and 1918, at the vortex of the Parisian avant-garde. He was called the “greatest poet of his generation” by André Breton, who in his Surrealist Manifesto of 1924 borrowed from Reverdy’s famous essay on the image: in the image, the two elements brought together to explode in a conflagration were more exciting the more distant they were from each other. Later, when that particular enthusiasm had died down for Breton, he used to quip that he himself could indeed be boring, but that Reverdy was “even more boring than me.”

REVERDY THE CUBIST

There was nothing boring about the texture of Reverdy’s early work and its distinctive crenellated shape and experimental form. His early poems earned him the reputation of being a cubist poet. Reverdy worked alongside painters for his entire life, and his close association with Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris is largely responsible for that label. In particular, Reverdy’s close collaboration with Gris lay at the origin of the poems of Au Soleil du plafond (Sun on the Ceiling), published in 1955 but begun in 1916 or 1917. Each poem refers to one of the Spanish painter’s still lifes, and the collaboration only ended with the death of Gris in 1927.

Several of Reverdy’s most characteristic poems have been gathered in this volume, translated and retranslated by various hands. Together, they constitute a kind of cubist still life, perceptible from many angles at once: “From 1910 to 1914 I learned the cubist lesson,” he said. Reverdy’s long poem “Carrés” (“Squares”) exemplifies this on a large scale. Here is its first cube shape, typical of his early poetry at its most sardonic:

The shameful mask hid his teeth. Another eye

saw they were false. Where is this happening?

And when? He’s alone, weeping, in spite of his

pride sustaining him, and he’s getting ugly. Since

it’s rained, the other one said, there’s spit

on my shoes. I’ve grown pale and wicked. And

he kissed the mask which bit him as it sneered.

[MAC]

Little by little Reverdy’s poetry grew still darker. As if to consecrate his break with his worldly life in Paris—which included an intense liaison with Coco Chanel—Reverdy set fire to a bundle of his papers on a Left Bank street corner in 1926, before choosing “voluntary exile” in the monastery town of Solesmes, with his wife, Henriette Charlotte Bureau, a seamstress by trade.

REVERDY THE RECLUSE

Increasingly melancholy and bitter, Reverdy lived as a recluse in Solesmes from 1926 onward, ever more estranged from society and eventually even from his own faith. The poem “Live Flesh,” placed in this edition in three juxtaposed translations, is as raw as Reverdy can be.

When German soldiers were posted in Solesmes, Reverdy, who had made “a pact with silence” and refused to publish anything during the Occupation, wrote the excruciatingly brutal Le Chant des morts—violent songs of all the dead that had long been “lodged in his throat,” unable to emerge. Published in 1948, with Picasso’s slashes of red surrounding Reverdy’s distinctive handwriting, they read like a funereal procession. He was certainly not a cubist always, any more than Picasso.

REVERDY AND US

The impact of Reverdy on American poets has been widely noted. During the fifties and sixties, he was translated by Kenneth Rexroth in New World Writing and in a Selected Poems published by New Directions, and by John Ashbery in The Evergreen Review. O’Hara memorably refers to him in his 1964 Lunch Poems—

My heart is in my

pocket, it is Poems by Pierre Reverdy

—and then goes on, in the same upbeat tone, to link his name to two other avant-garde writers:

everything continues to be possible

René Char, Pierre Reverdy, Samuel Beckett it is possible isn’t it

I love Reverdy for saying yes, though I don’t believe it

Ashbery (who also translated Reverdy’s novella Haunted House) spoke for the New York School as a whole: “Reverdy succeeds in giving back to things their true name, in abolishing the eternal dead weight of Symbolism and allegory so excessive in Eliot, Pound, Yeats, and Joyce.”

Along with longtime Reverdy devotees Ashbery, O’Hara, Ron Padgett, Rexroth, Patricia Terry, and Rosanna Warren, this volume also includes versions by some of the most respected American translators from the French—Dan Belm, Lydia Davis, Marilyn Hacker, Richard Howard, Geoffrey O’Brien, Mark Polizzotti, and Richard Sieburth—who were all invited to participate in this salute to Reverdy. From the very outset, this was a project conceived as a joint venture. Each translator was given a number of suggestions as to possible poems, chosen by the editor to represent the wide range of Reverdy’s work, from early to late.

Our special gratitude to Bill Berkson, for passing on to us the unpublished translations by O’Hara.

—Mary Ann Caws

Chronology

Born the...Dead the...

There are no events

There are no dates

There is Nothing

How marvelous

—Author’s Note, circa 1924

1889 September 11 (or 13), birth o

f the illegitimate child known as “Henri Pierre” (no surname specified) in Narbonne, registered as “born to an unknown father and mother.” Its mother, Jeanne Rose Esclopié, lives in Toulouse, abandoned by an errant husband, and its father, Henry Pierre Reverdy, owns a vineyard with his two brothers near Carcassonne.

1895 Henry Pierre Reverdy officially recognizes the six-year-old child as his own, while the boy’s mother, Jeanne Rose, finally divorces her husband. The child’s parents will marry two years later; his father described as “a wine merchant,” his mother as a “haberdasher.” Young Reverdy will do most of his primary and secondary schooling in Narbonne, while spending extended periods at his father’s vineyard, La

Jonquerole, at the foot of La Montagne Noire—a landscape to which his later poetry will repeatedly return.

1901 His parents divorce. He enters junior high school but is later held back a year.

1904 Death of his grandfather, Victor Reverdy—a sculptor and church stonemason like his ancestors before him. Reverdy, the most “plastic” of the French modernist poets, will consciously carry on the chiseled craft of his father’s side of the family.

1906 Age sixteen, drops out of Victor Hugo High School in Narbonne. Lives with his father, a colorful contributor to local newspapers, who homeschools him in an iconoclastic brew of anticlericalism, socialism, and anarchism.

1907 Major crisis in the wine industry leads to a strike by vineyard workers, riots, and bloody reprisals in Narbonne. His father goes bankrupt in the process.

1909 His father has a daughter with an unwed mother from Béziers, Denise Matignon, who is thirty years his junior. Another daughter will follow the next year, before the two marry.

1910 In October, having just turned twenty-one and exempted from military service, Reverdy leaves Narbonne for good. He takes the night train to Paris, where he soon settles in Montmartre, on rue Ravignan near the Bateau-Lavoir, the legendary gathering place of the cubist painters Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris. Reverdy forms an especially close (and fraught) friendship with the poet Max Jacob, thirteen years his senior. He eventually inherits the latter’s lodgings a little farther down rue Ravignan—the very room in which Jacob had seen an apparition of Christ on the wall in 1909, prompting his conversion to Catholicism. Reverdy’s early poetry will similarly be filled with haunted rooms.

Pierre Reverdy

Pierre Reverdy